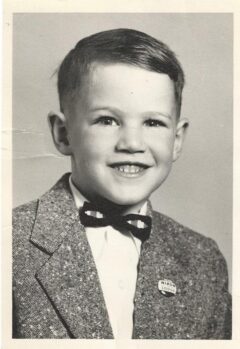

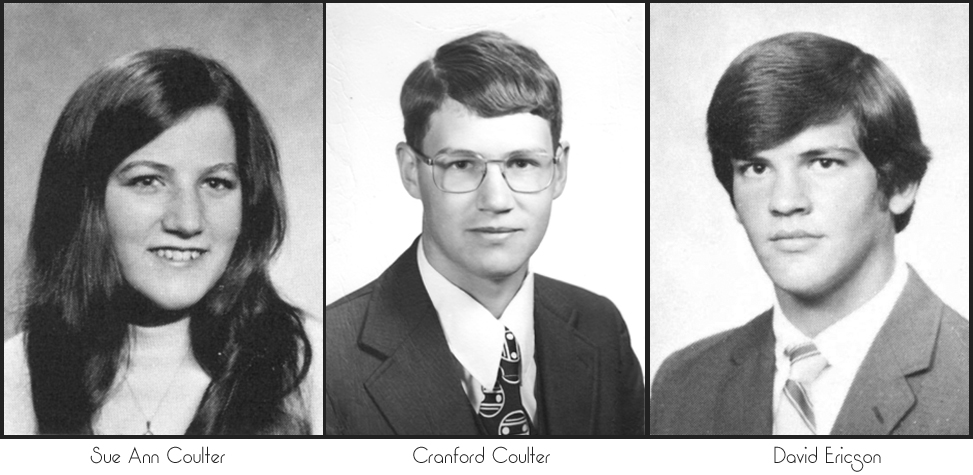

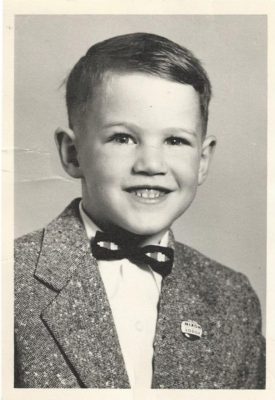

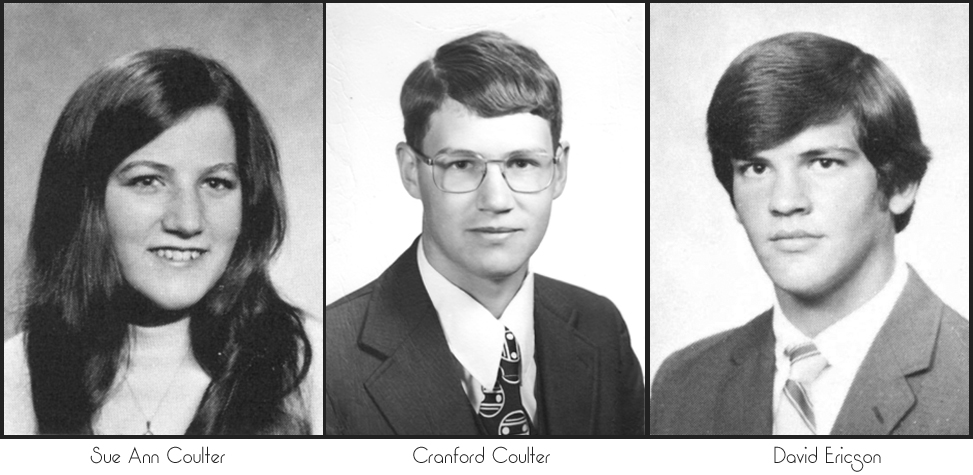

My playmates for the first six years of my life were my sister Sue Ann and our neighbor across the street, David Ericson. They were two years older than I was. I was the youngest of four in my family. David was the youngest of four in his family. There were other children in the neighborhood, but these were my closest friends and constant companions. Our family built a bigger house and moved two miles away in Golden Valley, MN, the summer between kindergarten and first grade, but we stayed in touch. We spent 4th of Julys together and got together around Christmas and did some other outings, as well. We ended up going to the same high school: Robbinsdale Senior High.

My playmates for the first six years of my life were my sister Sue Ann and our neighbor across the street, David Ericson. They were two years older than I was. I was the youngest of four in my family. David was the youngest of four in his family. There were other children in the neighborhood, but these were my closest friends and constant companions. Our family built a bigger house and moved two miles away in Golden Valley, MN, the summer between kindergarten and first grade, but we stayed in touch. We spent 4th of Julys together and got together around Christmas and did some other outings, as well. We ended up going to the same high school: Robbinsdale Senior High.

When we were little and playing cowboys and Indians, David always managed to get killed right outside his back door. He would lay there for a moment then he would get up and run into the kitchen and pour some ketchup on his face and lie back down; you know, to add bloody realism. The next time we would come by, he would still be lying there, but he would be scraping the ketchup off with potato chips and eating them. You just can’t waste food like that! There were children starving in Africa.

I have written about the Ericsons before. David’s parents, Les and Lois prayed for our family daily and brought us kids to church whenever my folks didn’t go, and to vacation Bible school, to their little Bible church in North Minneapolis. Lois particularly prayed for me daily from the time she heard my mom was pregnant with me until the day she died just a couple of years ago. I played with David’s toys while he was in school and my mom was working for the 1960 Census. The Ericsons’ house was the safest place I knew as a child. Playing with David’s Lincoln Logs in the middle of the living room floor with Mrs. Ericson in the kitchen was as good as life could get.

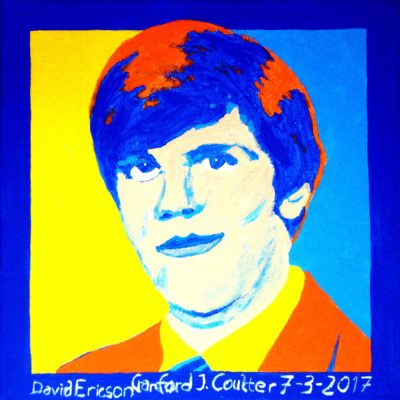

David grew up to be a serious, well-mannered, Christian, young man. He graduated RHS, Class of 1971. He decided to take a year off to do a short term missionary assignment with Wickliffe Bible Translators, helping his sister and brother-in-law, Jim and Carol Daggett, in Peru, instead of starting college. While there, he was accompanying a young girl on a flight to Quito, to get to a hospital for an emergency surgery. It was Christmas Eve. The flight went down and we did not know for weeks of what had happened. Finally, we learned that only one German girl survived. The plane had broken up in mid air in a bad storm. Pieces of the fuselage had fallen from the sky. Her mother died in the seat next to her. She was carrying her wedding cake on her lap. That may have helped save her. A tribe of natives who were known to be cannibals took her in and treated her wounds. She was finally found and rescued. So we lost David. He died on a mission of mercy. He was Les and Lois Ericson’s only son. Later that year, each of his three married sisters gave birth to sons.

When I was little I would tag along with Sue Ann everywhere. Of course, she was trying to tag along with our older sister, Alison, much of the time, so there were times they were trying to lose me. By the time Sue was in junior high, we were tight. I was a couple of inches taller than she was. She would take me to the 7th grade dances. Some people would assume that I was her date. Others would assume I was her twin brother. I would dance with all her friends. The 7th grade boys just sat there. I was in 5th grade and I was dancing with 4 or 5 girls at a time. I would help her with her math homework. By the time I was in junior high, she and I helped replace the useless student council with a Student Service Organization. We both served on the executive council. We were involved in the musical together. I was the third Ozian general. Sue Ann did make up.

Sue Ann & I became the ones that people would call if they were depressed and considering suicide. We appeared to be so stable. We were not always successful. There were attempts. Sometimes I would drink half a can of root beer, fill it up with six ounces of Scotch and drink that, just to go to sleep at night, in 8th grade. We played hard, too. We snow skied and water skied together. Sue Ann would waterbike while I would swim three miles around the lake in the summer. We read all the works of Hermann Hesse together, sometimes by firelight in the basement, while listening to psychedelic music on the Magnavox. I helped her on her English papers. She was a perfectionist, and I used to read dictionaries and the thesaurus. I tend to remember everything I read. She joined the yearbook staff in her junior year. I secretly helped her with that, even some of the all-nighters. I was still in junior high. The next year they had a poetry contest for the yearbook. I submitted a bunch of poems. They wanted to include several. Sue Ann already had me secretly working on staff. They made an exception and made me the only sophomore on staff and limited my published poems to one short one. We had the most intense year working together. The book won national awards, including one of my spreads, for which I had done the writing and she had done the most ruthless editing. I must admit, it is her voice in my head, editing, when I write. It is a painful process, but I tend to be succinct. I am told that people appreciate my style, even if they don’t always agree with my content.

We were so busy with things in high school that I didn’t see David much apart from family gatherings. We were all very involved with different things, but enjoyed our times together when we did see each other. It hit us hard when we got the news of his plane crash and we were in touch with his family daily, when it happened.

In the Spring of my sophomore year in high school I joined a fundamentalist, Baptist church, getting re-baptized with the whole born again thing. I was as serious with that as I am with anything in my life. We had our arguments over that, but she stuck by me. I still pulled all-nighters with her and helped her write some of her English papers for college. I even helped one of her girlfriends write a theology paper. It was kind of funny at one point. She had a prof. at Augsburg who was the husband of my British Lit. II teacher at RHS. They compared notes. I said there was good reason why our styles were so similar. Sue Ann had taught me how to write. And I edited her papers. They had a good laugh over a glass of Chardonnay that night.

By the time I was 21, three of the 100 kids in my 6th grade class had committed suicide. One had killed his sister and his parents with him. Another six friends from junior high and high school were gone by the time I was 24.

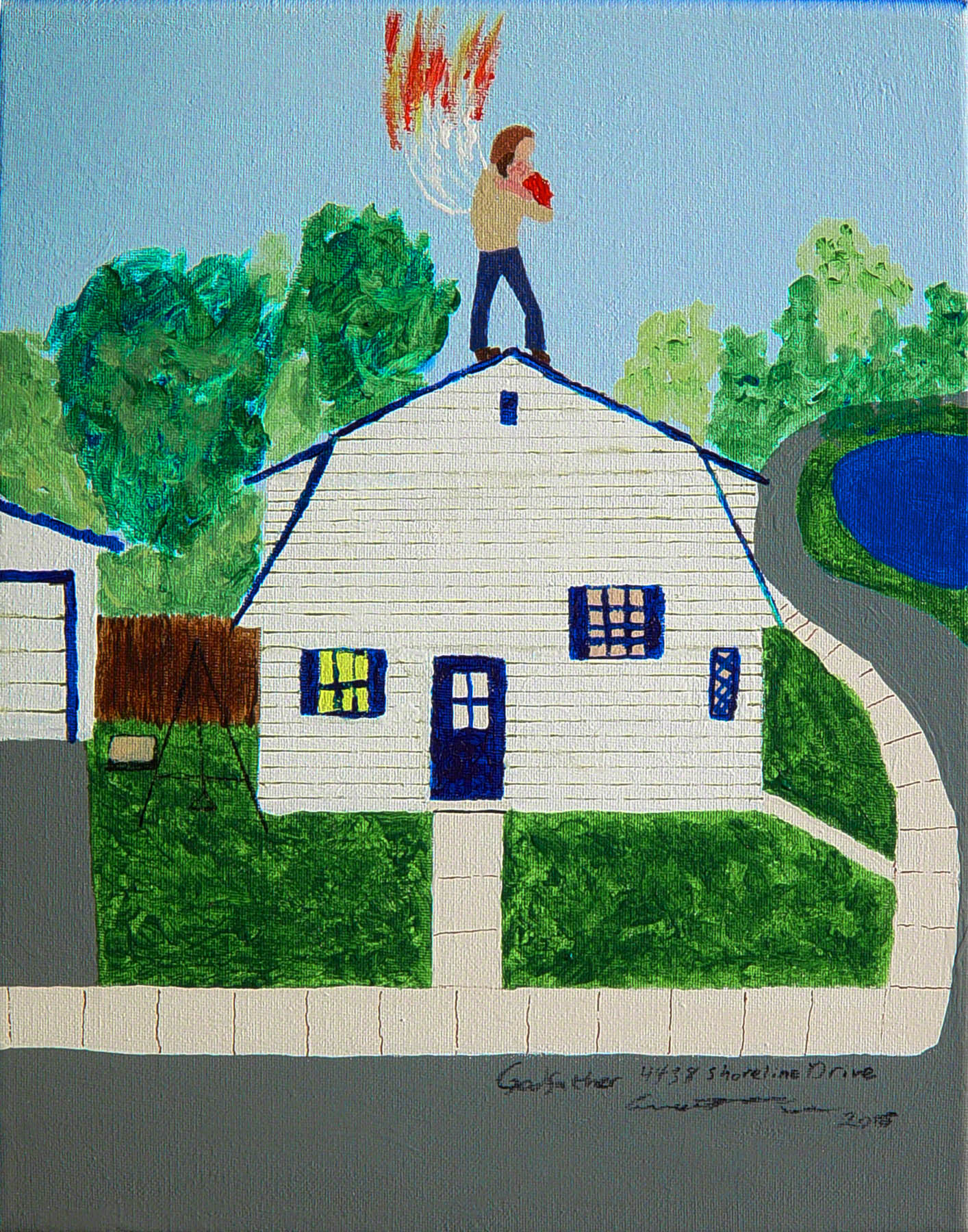

Sue got married in 1974. Bethann and I got married in 1975. Our friendship continued. She introduced Bethann to Creative Circle and I learned all sorts of needle crafts to help build the sales presentations. We stayed in constant communication, even though we were in PA and she and Bucky were in MN. Then communication fell off and I got a call from my older sister, Ali, that Sue Ann had checked herself into a rehab for alcoholism and was wanting everyone in the family to seek treatment as well. She had started the process by trying to do an intervention on our dad. While she was in treatment, she accused him of doing unspeakable things to us as children. My sister, Ali, would call me, at night, and ask me if these things were possible. She started the first phone call by asking me what the color of the living room was in our house on Shoreline Drive. That was the house where I was born. Then she asked me what my earliest memory was. I told her it was being carried through the crowded dining room in that house by Uncle Gordy. Uncle Gordy died when I was about two. I have the longest, most reliable memory in the family. She wanted to know whether what Sue Ann was accusing our dad of were at all possible. I told her, absolutely not! Apparently Sue Ann had been subjected to that regression “therapy” and given suggestions of false memories.

So I read the books about adult children of alcoholics that Sue Ann sent. When we visited MN and stayed with Sue Ann’s family, we went to AA with her. They would all come out and start chain smoking as soon as the meeting was over. It was like they had traded one addiction for another, or maybe for two: AA and smoking. She was more obnoxious about us joining AA than I had ever been about her being born again. But turnabout being fairplay, our friendship tolerated it. Unfortunately, she did have an addictive personality and that was a foreshadowing. We were out to MN for my dad’s wedding in 1994, we stayed at her house. Late at night she and her girls were talking to our girls about some of their Young Life activities. She said I could take part in the conversation. I said that of course I could. She talked about how they went out “witnessing” with a Muslim and a Christian paired together. I asked, “How could that possibly work, since Jesus said, ‘I am the way, the truth, and the life.'” She went ballistic. It was 0 to 70 with nothing in between. She was going to throw us out of the house then and there, on the edge of Minnetonka, at midnight, at about 0°, with no car, before cell phones. Bucky got involved. We came to a truce after he scored a few points. We got to stay the night and catch a ride to the train station the next day. She never spoke to me again. That was just five months after our mom had died. (I guess we exchanged pro forma Christmas cards for the sake of our children, after that.)

She told my dad a completely different story about what happened that night, a total fabrication. He wrote me lambasting me about it, without hearing my side of the story. I was completely blind-sided, since what I was accused of was so outrageous. Bethann had been there. She was equally shocked. My dad and I had had a rocky relationship. This was part of why my sister and I had been so close. It was part of our protection. My dad had physically thrown me out of the house when I was just shy of 16 just for asking him if he wanted to listen to a gospel quartet; actually it was at the lake place in Wisconsin, at night. My mom came after me and said, “If he goes, I go.” My dad said, “B.J., You know that isn’t fair. I will take you, even with him.”

Way to make a fellow feel loved, dad.

So, when I got that letter, I had had enough of the ups and downs, of the manipulations and intrigues. So rather than explain myself, I wrote my dad a letter telling him that he obviously had no interest in the truth. He had already judged and condemned me. I reminded him that he was a lawyer and he had taught me better; that people were to be considered innocent until proven guilty. I told him I had just had enough. I wasn’t going to play his games any more. I would grieve for him now. I didn’t want to hear about it when he died. So I lost my mom, my sister and my dad, in the space of six months. I did wonder why my dad believed her implicitly, after that which she had previously accused him. Later, I did try to reconcile with him, but he would have none of it.

In late 2000, I got the call from my sister, Ali, that Sue Ann had been found dead. I’m glad she got a hold of me before I checked my email with the subject line “Regarding my sister’s death” from my brother, who was too cheap to call. I flew out for her funeral. It took my sister, Ali, and I several months to uncover that she had committed suicide by a drug cocktail. My dad had told my brother and brother-in-law and the kids to keep it a secret. Sue had become addicted to gambling and had embezzled money from her boss. Her boss had just called her to talk about this. She had just separated from her husband. It was her old girlfriends from college that had the super unlock her apartment after she missed their dinner date, who discovered her.

It was just so awfully sad. I wish we had not fallen out so badly. I am not sure why I am writing this now. I just know that I love my sister. She was a wonderful person. She was a wonderful and creative mother. She was beautiful and talented. She had painted herself into a corner and couldn’t see any good way out. She should not have been alone with her illness.

So my earliest playmates have been gone for some time now. This month is Robbinsdale School District’s all year, all high school reunion and my class’s 40 year reunion. I can’t afford to go. The people I most would want to see are all dead. This is not where I thought I would be.

I just remember being so much happier and four and saying, “Alison, can you help Sue Ann and me cross the street so we can play with David?”